People who are homeless have a far greater risk of premature death than those who are not. In fact, they may die up to 20 years earlier than people who are not homeless.

The Ottawa Mission Hospice, also known as the Diane Morrison Hospice, was established in 2001. Until 2018, it was the only Hospice affiliated with a homeless shelter in North America. It was founded to provide care to those who are homeless grounded in:

– Compassion & kindness

– Mercy & dignity

– Community & belonging

– Unconditional acceptance

A Circle of Care

The Ottawa Mission Hospice is the nicest place I have ever lived. No one in my entire life has ever cared for me this much.

The Story of Tim

In 1999, a long-term shelter client named Tim was dying of AIDS. He also suffered from addiction, and he said his last wish was to avoid hospitalization and remain with his friends. Mission staff cared for him and he spent his final days at The Mission, surrounded by his friends.

“Our small chapel could not hold the people that came to pay their last respects. We provided felt markers for people to write their messages on the gray cloth-covered casket. Messages of sorrow, of hope and of love were written in English, French and Inuktituk. ‘He died with dignity’ — this was written in large letters on the side of his coffin. His friends carried him to his final resting place. Out of respect for Timmy, some of them placed their caps in his coffin. Dignity and respect had come to this homeless person. We are thankful for his life, we will miss him. May God keep him in His care!”

– Reflections by Staff on Tim’s Memorial, August 1999

The Founders of the Hospice

While he did not die in hospital, caring for Tim without a dedicated space and healthcare practitioners convinced The Mission’s Executive Director Diane Morrison that our shelter needed a Hospice.

Around this time, Dr. Jeffrey Turnbull and Wendy Muckle were forming Ottawa Inner City Health (OICH) to provide healthcare to those who are homeless and street-involved. Wendy, a registered nurse and healthcare manager, has now been OICH’s full-time Executive Director since its beginning. After progressive positions in medicine, Dr. Turnbull retired in 2017 to be OICH’s full-time Medical Director.4

“Diane Morrison was very receptive, and in The Mission we found a willing partner to improve end-of-life care for people who were homeless,” notes Dr. Turnbull.

A federal grant for a pilot project enabled OICH and The Mission to establish the Hospice, just as AIDS was devastating Ottawa’s homeless community. By bringing care to those experiencing homelessness directly, the project sought to show that this model of care would be more accessible, appropriate and cost-effective, and that it would improve clinical outcomes.

“I am still an Artist: I hear the Spirits.”

Normee’s Story

Normee was born in Great Whale River in Hudson’s Bay in 1948. A prolific Inuk painter and tapestry-maker, his work is included in collections within the National Gallery of Canada, the Canadian Museum of History, other public collections, and two children’s books: Arctic Childhood (1977), and Arctic Memories (1987).

As a child, Normee was forced to attend residential school. In 1971, he left the North to spend time with his sister and her family in Ottawa. Wanting to return later that decade, he found that his community had been flooded for a hydroelectric dam, so he stayed in the South.

Because of his experiences with trauma, Normee struggled with addictions and homelessness. When Dr. Turnbull found him living under a bridge in 2000, he convinced Normee to come to the Hospice, and he was the first patient to be admitted.

When he was first admitted, Normee was expected to live less than five weeks. But his will to live, combined with excellent care, allowed him to recover much of his health and resume his work as an artist in the last years of his life.

Sadly, two years before his death in October 2009, Normee lost both his legs, and eight fingers had to be amputated. After he died, 150 people attended his memorial service in our chapel, a testament to the love and respect Normee inspired within the homeless community and our shelter.

“The power of unconditional acceptance”

Itee’s Story

On March 5, 2019, a memorial service was held for Itee. Many of her family members, friends and care providers were in attendance — more than 60 people in all.

Itee was an Inuit woman who came from a large family in Nunavut. Two of her children, her sister, and many nieces and nephews came to her service, offering stories of unending love, warmth and kindness — stories that were echoed by friends and neighbour whose lives were touched by Itee.

Itee had borne significant burdens of colonialism and discrimination (and their unwelcome companions, tragedy and loss), but she had done so with remarkable courage, resilience and empathy towards others. This power of unconditional acceptance, supported by a merciful spirit, was very much in evidence at her service. Many spoke of Itee’s influence on them, which nourished their own ability to deal with loss. It was a moving experience to hear about the life of someone who, although often marginalized by others, nonetheless always smiled and greeted everyone with “Good morning,” and treated everyone with respect.

Itee loved to be outside. On her corner down the street from The Mission she would often spend time enjoying her independence and community. Everyone passing by that corner daily, including many of us at The Mission, will not forget this as we pass by her corner, remembering with fondness her smile and the sense of inclusion she embodied. Itee’s powerful lesson of openness and acceptance is her unending legacy at The Mission.

“An indomitable spirit”

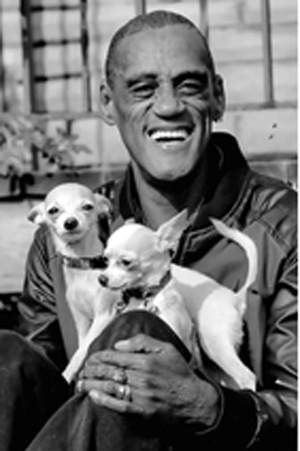

Henry’s Story

On April 11, 2019, another memorial service was held for Henry, who had also lived in our Hospice. Originally from New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, Henry was a gay man of Indigenous and African-Canadian descent. He loved many people, and also loved his two dogs, Mia and Minime, with complete devotion.

Sadly, he had incurred horrific physical, psychological and sexual abuse as a child, and carried deep trauma within him as a result. Despite this, his capacity for joy and his resiliency guided him through his life. And, as he would say when he encountered the indignity of prejudice resulting from ignorance, malice or discrimination, “I refuse to be insulted.”

Henry’s loving husband, Pierre, and over 75 close friends came together in the chapel to tell stories of how he, despite his own trauma and ill health, would do everything he could to support them, especially in times of crisis. One young trans person spoke movingly of how the despair engendered by prejudice and hostility caused her to contemplate self-harm, and how Henry eased this pain by supporting her unconditionally.

When Itee passed away, Henry brought flowers to her memorial service despite his own imminent passing.

Community meant everything to Henry. This could take many forms, such as sharing a meal or bearing witness to his profound faith in God in the last days of his life with Chaplain Timothy at his bedside. Henry’s indomitable spirit is his enduring legacy.